What happens in the musical scene during Domenico Scarlatti’s life and in the following decades after his death is a further weirdness related to the Neapolitan composer. While most of baroque composers have been forgotten due to a new musical and cultural sensitivity[1], Scarlatti has been appreciated by his contemporaries and by the main pianists over the 19th and 20th centuries.

What happens in the musical scene during Domenico Scarlatti’s life and in the following decades after his death is a further weirdness related to the Neapolitan composer. While most of baroque composers have been forgotten due to a new musical and cultural sensitivity[1], Scarlatti has been appreciated by his contemporaries and by the main pianists over the 19th and 20th centuries.

His spontaneity has been loved, opposed to Bach’s pompousness, as well as the apparent simplicity of the language, appreciated by amateurs[2] too, his taste for “cantabilità” and above all his technical-keyboard exploration that makes him a pioneer of 19th century pianism[3].

On the other hand, Scarlatti’s virtuosity and brilliance hide some features to musicians who perform Sonatas and give them an image of a bizarre and talented, but not very deep, composer.

His harmonic exploration[4] has often been “normalized” and his asymmetries have been misunderstood; his rhapsodic an improvised inspiration has often been considered messy. In an effort to classify his compositional style, some musicologists talk about Scarlatti’s Sonata like it is a proto-classical Sonata, without realizing that actually we have to look for the roots of Scarlatti’s compositions in the Italian and especially in the Neapolitan Toccata of 17th century.

We should also bear in mind that he did not write only for keyboard, indeed, but he composed operas, secular cantatas (during the years in Spain and in Portugal) and sacred music (among many, let me remind his last vocal work: the awesome Salve Regina, composed in 1756) that contains the typical originality and experimentation of Sonatas.

Let us try to explain Scarlattian weirdness looking for the two main stylistic influences within Sonatas: that which comes from the Andalusian popular tradition and that which comes from the Italian cultured tradition, considering that one of the main Scarlatti’s feature is heterogeneity. We know very few Sonatas with only one character. There are usually at least two or more issues and the deviation is often related to a few measures or to short parts of the piece; sometimes new hints are not developed but disappear as quickly as they have appeared.

SPANISH INFLUENCE

We owe Emilia Fadini the search of the Andalusian folklore elements that are in the Sonatas. Her contribute[5] inserted in “Domenico Scarlatti Adventures – Essays to Commemorate the 250th Anniversary of his death”[6] is a reference point for those who want to deepen the subject.

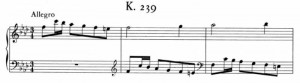

If we think about a Spanish influence, our thought immediately refers to that rhythm that we generally define “flamenco” and to Sonatas such as K239 in F Minor which is characterized from the beginning until the end by the typical impulse of the Spanish dance.

Sonata K239 (measures 1 to 3)

Sonata K239 (measures 11-12)

Sonata K239 (measures 15-16)

It isnotthe only rhythmic structure common to the Andalusian folk dances and to the Sonatas; Scarlatti also uses typical trends belonging to “Solea”, “Seguirya” and to “Seguidilla” that have more complex rhythmic cells that I will not treat on this occasion. But the Andalusian influence not only concerns the rhythm: above it covers the harmonic and melodic structure, the pronunciation elasticity, the formal organization, the use of repetition.

Flamenco style comes from “Cante Jondo”, developed from 15th century in the south of Spain and originated by the melting of the ancient musical Andalusian tradition, Byzantine liturgical song elements, Oriental features from the Arabic culture and suggestions brought by gypsies coming to Spain from the East. “Jondo” means “deep” and testifies of a plaintive song, that screams desperation and impotence.

Scarlatti takes from “Cante”, among other, the following elements, replicating them in a typical compositional structure belonging to the Italian tradition:

– Freedom of the introductions. Scarlatti’s Sonatas often start with an introduction disconnected from the rest of the composition: a whole phrase, a little theme, an arpeggio, a simple gesture. In the flamenco the guitar usually introduces chants and dances freely, even if the writing uses traditional time marks.

As for other features, the aim of the performer should be to put in evidence the different character of the introduction and not to integrate it with the rest of the piece, especially if it is quite different and “strange”.

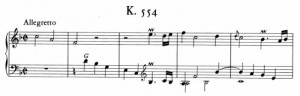

The Sonata K554 (F major) starts with 2 measures and half (a succession of descending thirds) that never come back anywhere in the piece.

Sonata K554 (measures 1 to 5)

The Sonata K104 (G major) opens with two different themes (from measure 1 to 14 and from 15 to 25) and then takes a completely different direction.

Sonata K104 (measures 1 to 33)

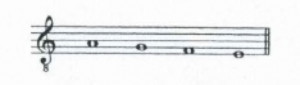

– Scales and Andalusian cadences. Spanish claim to have maintained the theoretical principles of the Greek musical system founded on descending tetrachords (two tones and a half from the high to the low). Pure flamenco, as Spanish musicians call it, adopts as harmonic base the descending tetrachord named “Doric”, with a half tone between the third and the fourth degree[7].

The Andalusian tetrachord[8]

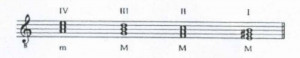

The common realization of the tetrachord[9]

We can see in the cadence that the succession of four chords of third and fifth could involve a series of consecutive fifthsand the use of interval of a tone and a half between the penultimate and the last triad.

Scarlatti often uses scales and Doric cadences in his Sonatas and it can be easily noticed that, if this is not contextualized or from the point of view of the tonal harmony, this method can sound weird or even incorrect.We can also add that in the Sonatas sometimes the flamenco harmony integrates with the “suonar pieno” style, that I will further explain, learned by Scarlatti in Rome by Gasparini.

One example, among many, of the use of the Spanish tetrachord: in the Sonata K6 in F major we can find the “flamenco cadenza” from measure 18 to 25.

Sonata K6 (measures 14 to 25)

Sonata K6 – Harmonic pattern of measures 18 to 25[10]

Sonata K24 (measures 8 to 11): hard chords (measures 12-13). We can see also the Andalusian tetrachord in the bass line (B-A-G♮-F♯between measures 11 and 12)

– Melodic proceedings. Some typical features of Andalusian musicarethe intensive use of melismatic features, the repetitions of a single note (sometimes accompanied by higher or lower appoggiatura) or of some small musical elements with an expressive purpose, chromaticism and expressive intervals.

We can notice them clearly in the following examples.

Sonata K263 (measures 41 to 46): melismatic phrases

Sonata K193 (measures 85 to 101): repetition of a little ornament (from measure 86 to 99)

Sonata K426 (measures 134 to 142): obsessive repetition of chords from measure 138 to 153

Sonata K426 (measures 143 to 160): obsessive repetition of chords from measure 138 to 153

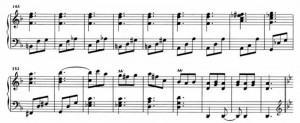

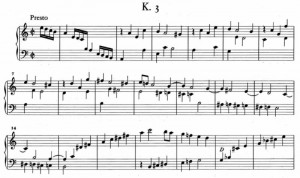

Sonata K3 (measures 1 to 20): descending chromatic scale from measure 10 to 15 in the lower staff and diminished seventh arpeggios (15-16 and 19-20)

[1]Emblematic, among many others, are the stories about Antonio Vivaldi, appreciated in life, forgotten and rediscovered only in the 20th century and about Johann Sebastian Bach that was appreciated, but already considered a conservative by his contemporaries and neglected for decades after his death. Another supreme musician, George Philipp Telemann, began to re-emerge (and only partly) starting from the second half of the twentieth century

[2]When we speak about “amateurs” we must not think about the negative meaning that the term has acquired in our culture. In the 18th century the “amateur” was usually a person of high rank and good education, that practice music (or dance, or poetry) often at a great level for their own pleasure and not for material need. Among “amateurs” there were probably many musicians’ customers (“customers” in the sense of those who could afford to pay tuition and buy the then expensive sheet music). Composers often made explicit reference to the amateurs: “Don’t expect, amateur or Professor, that you’re …” writes Domenico Scarlatti in the preface to “Essercizi”; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach dedicates many of his compositions to “Kenner und Liebhaber” (competents and amateurs) and mentions several times the amateurs in his Versuch; Johann Sebastian Bach in the preface of “Inventionen und Sinfonien” turns to “…harpsichord enthusiasts…”

[3]Scarlatti was an innovator of keyboard technique. He developed the speech of composition to the farthest of the keyboard, he gave equal dignity to the ten fingers and developed the use of the forearm and arm (up to that time keyboardists showed off great virtuosity, but mostly with steady hand)

[4]In the famous dialogue, reported by Burney, between Scarlatti and Alexander Ludwig the Augier, an Austrian physician, cultured and refined traveller who was in Madrid probably towards the end of 1755, (Roberto Pagano: “Alessandro e Domenico Scarlatti. Due vite in una” – Mondadori 1985, p. 495) Domenico says to be conscious of having broken almost all rules of composition, but, given that his exceptions did not offend the ear, then he believed “that there were no rules worthy of the attention of a man of genius, than not to displease the only way by which music is the subject”

[5]The title of the contribution is: “Domenico Scarlatti: integration between Andalusian style and Italian style”

[6]The work was edited by Massimiliano Sala and W. Dean Sutcliffe and published by “Ut Orpheus” in 2008

[7]The medieval theory overturns the system: the tetrachords are processed in ascending with the same succession of tones and half-tones and then the Spanish “Doric” tetrachord becomes the “Phrygian” tetrachord and vice versa

[8]From: “Domenico Scarlatti Adventures – Essays to Commemorate the 250th Anniversary of his death” – Page 160

[9]Ivi, page 160

[10]Ivi, page 163

“Traduzione a cura della prof.ssa Fernanda Carere”

Questo post è disponibile anche in: Italian

English

English Italiano

Italiano

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.