After a long time I’m taking back my articles with some writings about Domenico Scarlatti and his repertoire for keyboard. I’ve just finished to record my second CD dedicated to Scarlatti’s Sonatas; it will be out at the end of July, published by “Da Vinci Publishing”.

After a long time I’m taking back my articles with some writings about Domenico Scarlatti and his repertoire for keyboard. I’ve just finished to record my second CD dedicated to Scarlatti’s Sonatas; it will be out at the end of July, published by “Da Vinci Publishing”.

My papers will refer to the text of the lecture I had on November 2017 at the Music Academy in Gdansk (Poland) in the context of a meeting dedicated to the Italian art in the baroque age.

The informations in next articles are taken by:

- Ralph Kirkpatrick – Domenico Scarlatti (Princeton University Press-1953)

- Roberto Pagano – Alessandro e Domenico Scarlatti-Due vite in una (Mondadori-1985)

- AAVV – Domenico Scarlatti Adventures-Essays to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his death (Ut Orpheus Edizioni-2008)

- Enrico Baiano/Marco Moiraghi – Le Sonate di Domenico Scarlatti-Contesto, testo, interpretazione (Libreria Musicale Italiana-2014)

- Emilia Fadini – La grafia dei manoscritti scarlattiani: problemi e osservazioni (Leo S. Olschki Editore-1990)

- Pinuccia Carrer, Emilia Fadini, Maria Cecilia Farina, Marco Farolfi, Angela Romagnoli, Mauro Squillante, Sergio Vartolo – Forewords to the CD collection “Domenico Scarlatti-Complete Sonatas” (Stradivarius)

INTRODUCTION

About thirty years ago I performed my first Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonata (it was K1 in D Minor) and I did not imagine how rich and diverse the scarlattian word could be. I already knew a lot of Sonatas at that time; most of them were brilliant, thanks to piano recording and some accordion colleagues’ performances and, as anyone, I was fascinated by the lightness and the brilliance of those works of art.

About thirty years ago I performed my first Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonata (it was K1 in D Minor) and I did not imagine how rich and diverse the scarlattian word could be. I already knew a lot of Sonatas at that time; most of them were brilliant, thanks to piano recording and some accordion colleagues’ performances and, as anyone, I was fascinated by the lightness and the brilliance of those works of art.

I went on playing Sonatas in my programs over the years and little by little I realised it did not deal with performing brief pieces of music to introduce my concert or studying them to focus on the technique. There was something else and my curiosity to discover more was surely the main motivation that pushed me to deepen my early repertoire study.

A very fortunate series of encounters with Roberto Pagano, Marco Farolfi, Luca Oberti, Enrico Baiano and, above all, Emilia Fadini, helped me in my research and today I am here to tell you about the multifaceted nature of Scarlatti’s Sonate and about how I work to adapt them to accordion.

Emilia Fadini, harpsichordist, pianist and musicologist, introduces the recording of Domenico Scarlatti’s “complete works” highlighting that, on the contrary of what happened to J.S. Bach, judged by his contemporaries as a conservative composer and forgotten for fifty years since his death, the Italian composer has always occupied a preminent place in the music scene, during his life and in the following decades and centuries.

The aspect that impressed the most to the major pianists throughout the eighteenth and even the nineteenth centuries lies in the technical exploration applied by Scarlatti to the keyboard, that upset the writing criteria that had been used up to that time.

This attention for virtuosity allowed to keep alive the interest in Scarlatti over the centuries, but, on the other hand, obscured, at least partially, the manifold characters that breathe life to the Sonatas in addition to the instrumental brilliance.

The Scarlattian world is full of “affetti” and suggestions. In his Sonatas we can find echoes of Italian counterpoint learned by his father Alessandro, dance rhythms, Italian “cantabilità”, Spanish influences from Andalusia and, often, these features change every few bars.

The modern performer has to identify and, above all, to express clearly every different “affetto”, without focusing exclusively on lightness and brilliance, even if there are plenty in the Sonatas.

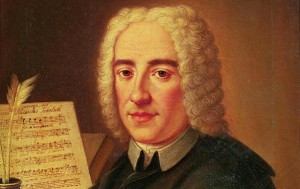

SOME BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

Domenico Scarlatti’s figure is surrounded by an air of mystery. We have a lot of information about J.S. Bach and Handel’s lives who, like him, were born in the fortunate year 1685, at least for what deals with music. We do not know much about Scarlatti’s education instead, even less about the long period he spent between Portugal and Spain, where he died in 1757.

Domenico Scarlatti’s figure is surrounded by an air of mystery. We have a lot of information about J.S. Bach and Handel’s lives who, like him, were born in the fortunate year 1685, at least for what deals with music. We do not know much about Scarlatti’s education instead, even less about the long period he spent between Portugal and Spain, where he died in 1757.

He was born in Naples, that was already a very problematic city, but characterized by the presence of four Conservatories and so well known for its intense music life and where he probably received his first education by his father Alessandro, one of the main composers of the time, and by some relatives, most of them committed to musical activities.

We can imagine that, despite his father’s frequent absence, who was connected to the theatre and its commitment, Domenico received a very strict education by a musician who considered music as a “mathematics’ daughter”.[1] We presume that he came in contact with the main Neapolitan musicians of that time very early and with Francesco Gasparini e Bernardo Pasquini, both active in the Roman scene, thanks to Alessandro’s acquaintances.

Some documents and stories allow us to learn about early Domenico’s trips to Italy. In 1705 he was sent by his father, who wanted to introduce him at Ferdinando de’ Medici’s court, in Florence and, in the same year, considering his father’s intentions failure, he moved to Venice, where he lived about until 1709. In Venice he surely heard Vivaldi’s music in the Chiesa Della Pietà and met Gasparini, who was at the peak of his fame. Two interesting stories belong to this period : the first one is reminded by Charles Burney[2]; he describes Domenico’s first meeting with Thomas Roseingrave, who later would have become his apostle in England and who talks about the “evil virtuosity” of the Italian musician. The other one, told by Mainwaring[3], tells about a meeting between Handel and Scarlatti. He refers to an event, probably at the beginning of the year 1709, when Cardinale Ottoboni organised a challenge with organ and harpsichord between the two musicians. We hear of the German performer’s superiority with the organ, but we know also that Scarlatti’s expression of elegance and lightness with harpsichord had been extremely appreciated.

At Ottoboni Palace, Domenico surely came in contact with Corelli’s music and he probably met plenty of musicians who were in the eternal city at that time: besides the already mentioned Gasparini and Pasquini, we can name Caldara, Bononcini and Zipoli among many others.

He left his sign in Rome as a singer[4] and he probably succeeded, by replacing his father, as the exiled Queen Maria Casimira of Poland’s Chapel Master. He wrote musical works, orators and serenades, most of them unfortunately lost and he established contacts that would have led him to Portugal and to Spain in November 1719.

In Portugal he was hired as “King Giovanni V’s compositor” with the additional assignment of Infanta Maria Barbara and younger king’s brother don Antonio’s musical education. Domenico probably returned to Italy several times and he maybe visited Paris and London as well, but since 1729, when Maria Barbara married the crown prince of Spain Fernando delle Asturie, he followed his very talented pupil in Spain and he remained at the Spanish court until his death.

[1] From a letter by Alessandro Scarlatti to Ferdinando de’ Medici, May 1, 1706 (Kirkpatrick, p. 24)

[2] An amateur musician, traveller, cultured and curious, Charles Burney (1726-1814) undertook two long journeys (in 1770 in France and Italy and in 1772 in Germany and in the Netherlands) where he collected material for his General History of Music, with which he posed the Foundation of modern musicology. From these trips were born two famous books: The Present State of Music in France and in Italy (London, 1771) and The present State of music in Germany, the Netherlands, and the United provinces (London, 1773)

[3] John Mainwaring (1724-1807) was the first biographer of Georg Friedrich Händel

[4] It seems that in June 1717 in the Palace of Princess Albani “Mr. Scarlatti the young, great musician, played the harpsichord and sang”. (Baiano-Moiraghi, p. 5)

“Traduzione a cura della prof.ssa Fernanda Carere”

Questo post è disponibile anche in: Italian

English

English Italiano

Italiano

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.