Early music for a modern instrument

With this article we inaugurate a new space in which, on a monthly basis, we will deal with accordion in relation to early music.

Giorgio Dellarole, concert performer and teacher, will edit this work. Mr. Dellarole, over the past decade, has devoted most of his energies to the study and interpretation of the Baroque, late Baroque and Classical repertoire, studying with Emilia Fadini, Marco Farolfi, Luca Oberti and collaborating with some specialists such as Alessandro Tampieri, Alessandro Palmeri, Michele Andalò, Fiorella Andriani and Saverio Villa.

Preamble

If we exclude sporadic backgrounds, we can consider that the systematic study of the ancient repertoire and the research of a coherent and credible interpretative mode sink their roots in a cultural movement initiated by the publication of the essay written by Arnold Dolmetsch “The Interpretation of the Music of the XVII and XVIII Centuries” (London, 1915).

If we exclude sporadic backgrounds, we can consider that the systematic study of the ancient repertoire and the research of a coherent and credible interpretative mode sink their roots in a cultural movement initiated by the publication of the essay written by Arnold Dolmetsch “The Interpretation of the Music of the XVII and XVIII Centuries” (London, 1915).

The keyword for the pioneers of early music is “authenticity”, a term introduced by Dolmetsch that, implicitly, labels as “infidel” the interpretative tradition in vogue in the early XX century (1) and that therefore is in clear contrast with it.

Based on a reconstruction of ancient instruments (at the beginning especially the recorder and the viola da gamba) the concept of “authenticity” inspires a rather elitist movement, which arouses controversies and excludes the use of non-original instruments.

Over the decades, interest on this matter increases and knowledge in interpretative, organologic and technical field are enhanced. The development of musicology, starting from the immediate post-war period, provides a further impetus to researches and puts in crisis some of the “dogmas” that characterised the first movement of early music, causing in this way the mutation of the basic concept, which turns into “historically informed performance”.

In October 2007, in an interview published by the magazine “Sistema Musica” of Turin, Fabio Biondi, violinist and conductor specialized in the interpretation of early music, says to Diego Marangon: “The study of how the early music repertoire was played has achieved a great victory, by sharing its history and language. Now, it has to win over the preconception of the instrument. I can envisage a great coalition coming about in the future, guided both by a knowledge of the score and the musician’s awareness, where Bach can be played equally well on the harpsichord or the accordion.”

Biondi in his speech affirms that with “knowledge of the score” and with the awareness of the performer even with accordion it is possible to play Bach; anyway, I would not dwell on this aspect.

I would rather prefer to concentrate my attention, and I will do it in my next article, on the emphasis that is placed on the words “knowledge” and “awareness”, in which, in my opinion, it resides the key for a modern and correct interpretation of the ancient repertoire (2).

Knowledge and awareness

In my opinion, it happens sometimes that performers are superficial when they play the ancient repertoire.

I would say that it is common practice, not only among accordion players, to include in a concert program some Baroque compositions which are performed with the spirit generally adopted to deal with a study on articulation, looking to imitate the brilliance of the harpsichord touch.

Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonatas are very popular among keyboard players as well as being emblematic in this sense.

It is true that the lightness is a feature of the harpsichord, but it is forgotten that there is an infinite variety of articulations (starting from the “staccato” to the “super-legato”) at harpsichordists disposal.

Speaking of language, there is no denying that the virtuosity, even extreme, is an element widely used by Scarlatti, but this fact does not exclude that in his Sonatas there are all the characters that feature in the contemporary Opera, from the brightest to the most pathetic and tragic.

If I had to mention the main feature of Scarlatti’s Sonatas, I would not speak about virtuosity, but rather about the presence of two or more characters that often are in rhythmic, melodic or harmonic conflict.

Unfortunately, many performers try to level out differences rather then emphasize them.

It is really important to be aware of the work that you are dealing with and you have to be informed, to know the context in which it was written and understand the “language” spoken by the author. This is especially difficult when you deal with the Baroque repertoire because it has not come down to us with a linear path, but it has been shelved before, and then revisited/misrepresented in the light of romantic aesthetics and only recently rediscovered and more carefully and respectfully examined. There are several problems to face:

- It is very old music, written for old instruments that nowadays, probably, have been modified in their structure and because of this, they sound differently in relation to the past

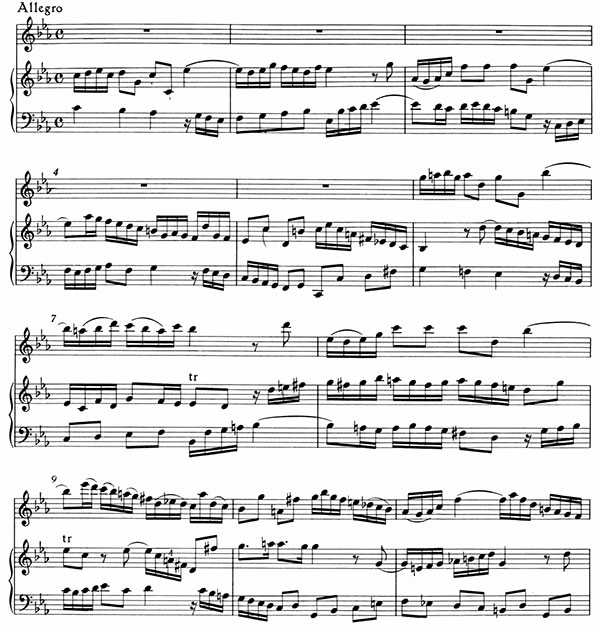

- For several reasons, the writing, in particular the one concerning keyboard instruments, is extremely essential. Infact it lacks of “legature” that we are used to find in the most recent scores. Moreover, often ornaments are implied and the diffusion of the practice of improvisation prevents us from knowing exactly what and how music sounded at that time. You can compare the violin and the harpsichord staves in the Allegro (2nd part) of the Sonata in C minor BWV1017 by Johann Sebastian Bach, taken from an Urtext edition: in bar 9 the sixteenth notes of violin (on the upper staff) are grouped while the same excerpt for the harpsichord (bar 4) shows no sign of articulation; similarly the sixteenth notes of the violin in bar 7 and the semiquavers of the harpsichord in bar 2

- Manfred Bukofzer in his “Music in the Baroque Era” (New York, 1947) states that it is not possible to simplify a century and a half of music that has been characterized by an extreme variety. Among a Toccata of Gabrieli, one of Frescobaldi or Bach, there are the same differences that exist between a Sonata for piano of Beethoven and one of Rachmaninoff. In order to consciously play the different scores, you have to know the different characteristics of schools, eras and styles that characterize the Baroque period.

- Whenever you make a transcription from harpsichord to the piano or to the accordion, many opportunities show up, but you have to act with caution and discernment because in this case problems multiply

In order to solve the first three points I think it is enough to take seriously what you do and to get appropriate information. Given the vastness of the subject it is not an easy thing, but it can be done. The documents are no longer the preserve of a small elite as it was the case at the time of the pioneers of early music, but they are at everyone disposal. Sources can be traced by consulting treaties, letters, prefaces of scores and everything that helps to frame the historical context or by relying on those who have done an accurate study and have proposed their results (3).

The acquisition of the necessary knowledge provides, among other things, the ability to understand the original sources or Urtext editions that reproduce them and the fact not to be forced to adopt revisions or transcriptions that often do not help to understand the meaning of the scores.

Concerning the fourth point, I quote the words that Marco Farolfi (4), harpsichordist, pianist and teacher, as well as specialist of the early repertoire, used to describe the work that, over the years, we have done together. With this thought, which I fully support, I close my first speech on “strumentiemusica.com”. I am grateful to Gianluca Bibiani for the space he offered me and for the esteem that he has expressed, which of course I reciprocate.

“Playing early music repertoires on modern instruments is both quite popular and controversial. From one point of view we can say that the instrument has the role of a “mediator” which conveys the musical message and we can therefore consider it as an intermediary between the formation of musical ideas and interpretation of the musician. If the instrument become a “medium”, the music gets the “matter”. But this does not mean that the modern “instrumental mediator” will not take the greatest possible care to respect the style and character of the musical pieces. The study of musical language and methodology means that it is possible to express the feelings of early music using either original or modern instruments. During my work with Giorgio I discovered that the musical composition was always in the foreground and the “modern mediator” may be the perfect way to perform these compositions. The use of historical instruments to play early music can help to recreate the atmosphere which the composer would have wanted. But today after the passage of hundreds of years and the use of modern instruments we can say that any instrument can be adapted to any musical style and no one can say which instrument is more appropriate if it doesn’t prevail on the nature and on the contents of the music that it creates.”(1) At that time and even today the late-Romantic esthetic dominated the music scene and influenced the performance of Baroque pieces

(2) With “ancient repertoire, in a very personal sense, I refer to the music written since the birth of keyboard instruments until Mozart and Haydn

(3) In the next article I will talk about the treaties and of the most important texts; for the moment I simply suggest to read “Il clavicembalo”, Bellasich, Fadini, Granziera, Leschiutta – EDT (2005) that, in its four parts, presents the ancient keyboard instruments, the temperaments, the mensural notation and the different historical fingerings

(4) About Marco Farolfi: “Domenico Scarlatti – Complete Sonatas” – Stradivarius – Vol. 6 Domenico Scarlatti - Sonata in F minor K462 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkSj4802TyQ) and Sonata in F minor K463 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CECXEOWU6l8)I am grateful to Marta Cogotti for her translation

Questo post è disponibile anche in: Italian

English

English Italiano

Italiano

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.