Le Sonate di Domenico Scarlatti: un universo multiforme e pronto ad essere riscoperto – 2 (English version of this article)

Ciò che accade nel mondo musicale durante la vita di Domenico Scarlatti e nei decenni successivi alla sua scomparsa è un’altra delle “stranezze” legate al compositore napoletano. Mentre una buona parte dei compositori barocchi viene infatti dimenticata a causa dell’affermarsi di una nuova sensibilità culturale e musicale[1], Scarlatti è apprezzato dai suoi contemporanei e dai maggiori pianisti lungo il Settecento e durante tutto l’Ottocento. Piacciono la sua spontaneità, contrapposta all’ampollosità bachiana, l’apparente semplicità del suo linguaggio, apprezzabile anche dai “dilettanti”[2], il suo gusto per la cantabilità e, soprattutto, la sua esplorazione tecnico-tastieristica che ne fa un antesignano del pianismo ottocentesco[3].

Ciò che accade nel mondo musicale durante la vita di Domenico Scarlatti e nei decenni successivi alla sua scomparsa è un’altra delle “stranezze” legate al compositore napoletano. Mentre una buona parte dei compositori barocchi viene infatti dimenticata a causa dell’affermarsi di una nuova sensibilità culturale e musicale[1], Scarlatti è apprezzato dai suoi contemporanei e dai maggiori pianisti lungo il Settecento e durante tutto l’Ottocento. Piacciono la sua spontaneità, contrapposta all’ampollosità bachiana, l’apparente semplicità del suo linguaggio, apprezzabile anche dai “dilettanti”[2], il suo gusto per la cantabilità e, soprattutto, la sua esplorazione tecnico-tastieristica che ne fa un antesignano del pianismo ottocentesco[3].

Il rovescio della medaglia è che l’estremo virtuosismo e la brillantezza nascondono, agli occhi dei musicisti che le affrontano, gli altri caratteri presenti nelle Sonate e danno di Scarlatti l’immagine di un compositore agile, bizzarro, ma poco profondo.

La sua esplorazione armonica[4] viene spesso “normalizzata”, si “raddrizzano” le asimmetrie e si giudica disordinata quella che è invece un’ispirazione rapsodica e legata all’improvvisazione.

Nel disperato sforzo di inquadrarne la struttura compositiva, alcuni musicologi credono di vedere nella Sonata scarlattiana l’antesignana della forma-sonata classica, senza capire che le sue radici vanno ricercate piuttosto nella Toccata napoletana del 17º secolo e che le sue peculiarità sono presenti anche nel resto della produzione scarlattiana.

Domenico non scrisse solo Sonate per tastiera, ma compose Opere, Cantate (anche durante gli anni in Portogallo e in Spagna) e musica sacra (ricordiamo il meraviglioso Salve Regina del 1756) e tutti questi lavori contengono in qualche misura l’originalità e il gusto per la sperimentazione tipici delle Sonate.

Proviamo ora a spiegare le “stranezze” scarlattiane analizzando le due principali correnti stilistiche presenti nelle Sonate: l’influenza spagnola, proveniente dalla tradizione popolare andalusa e l’influenza della tradizione colta italiana, assorbita da Domenico durante gli anni della formazione a Napoli, Venezia e a Roma.

Nel cercare di individuare le influenze stilistiche non dimentichiamo che una delle caratteristiche principali delle Sonate è la loro eterogeneità. Ci sono pochissimi brani con un andamento univoco e spesso troviamo due o più caratteri che appaiono e scompaiono a volte nell’arco di poche misure.

L’INFLUENZA SPAGNOLA

Dobbiamo soprattutto ad Emilia Fadini l’identificazione degli elementi del folklore andaluso nelle Sonate. Il suo contributo[5], inserito in “Domenico Scarlatti Adventures – Essays to Commemorate the 250th Anniversary of his death”[6], è un punto di riferimento per quanti vogliano approfondire l’argomento.

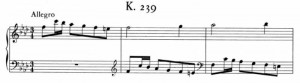

Se pensiamo ad un’influenza spagnola il nostro pensiero corre solitamente all’impulso ritmico che definiamo, generalizzando, “flamenco” e che ritroviamo in Sonate come la K239 in Fa minore, caratterizzata dall’inizio alla fine dal tipico ritmo di danza spagnola accompagnata dalle nacchere.

Sonata K239 (battute da 1 a 3)

Sonata K239 (battute 11-12)

Sonata K239 (battute 15-16)

Non si tratta dell’unica struttura ritmica comune al folklore andaluso e alle Sonate; Scarlatti usa anche elementi tipici della “Solea”, della “Seguirya” e della “Seguidilla”, che hanno schemi ritmici più complessi che non analizzerò in questa occasione.

Ma l’influenza andalusa non riguarda solo le strutture ritmiche: è molto più ampia e coinvolge l’armonia e le line melodiche, l’elasticità della pronuncia, l’organizzazione formale e l’utilizzo sistematico della reiterazione.

Lo stile “flamenco” deriva dal “Cante Jondo”, sviluppatosi a partire dal 15º secolo nel sud della Spagna e fondato sull’unione di antiche tradizioni andaluse, elementi tratti dalla liturgia bizantina, suggestioni orientali portate in Spagna dagli arabi e modalità espressive tipiche delle popolazioni zingare giunte nella penisola iberica dall’Europa dell’est.

“Jondo” significa “profondo” e testimonia di un canto struggente che esprime disperazione e impotenza.

Scarlatti prende dal “Cante”, tra gli altri, i seguenti elementi, inserendoli in una struttura compositiva tipicamente italiana:

– Introduzioni libere. Le Sonate di Scarlatti spesso iniziano con un’introduzione non collegata al resto della composizione: una frase, una piccola linea melodica, un arpeggio, a volte un semplice gesto. Nel “flamenco” la chitarra introduce solitamente il canto e la danza con libertà, anche se la scrittura utilizza valori definiti, inquadrati dalle tradizionali indicazioni metriche.

Come per gli altri elementi (di qualunque provenienza) che compongono il caleidoscopio delle Sonate, anche per le introduzioni, a maggior ragione se molto diverse dal resto della composizione, l’obiettivo dell’esecutore dovrebbe essere quello di individuarne il carattere e di esprimerlo chiaramente e non, come purtroppo si fa abitualmente, di cercare di uniformarle al resto del brano.

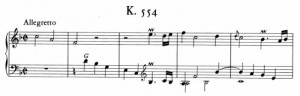

La Sonata K554 (Fa maggiore) comincia una successione di terze discendenti che non verrà più ripresa nel resto del brano.

Sonata K554 (battute da 1 a 5)

La Sonata K104 (Sol maggiore) si apre con due diverse proposte (dalla battuta 1 alla 14 e dalla 15 alla 25) per poi svilupparsi in una direzione completamente nuova.

Sonata K104 (battute da 1 a 33)

– Scale e cadenze andaluse. I musicisti “flamenchi” sostengono di aver mantenuto I principi teorici del sistema musicale greco, basato sui tetracordi discendenti (due toni e mezzo dall’acuto al grave). Il flamenco “puro”, come viene definito, adotta come base armonica il tetracordo discendente “dorico”, caratterizzato da un semitono di distanza tra il terzo e il quarto grado[7].

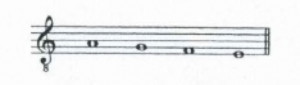

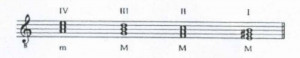

Il tetracordo andaluso[8]

La normale realizzazione del tetracordo andaluso[9]

Notiamo che la successione di quattro accordi in stato fondamentale e gli intervalli presenti tra il terzo e il quarto accordo possono portare a movimenti basati su quinte parallele o all’uso di intervalli di seconda eccedente.

Scarlatti inserisce spesso la scala “dorica-flamenca” nelle sue Sonate ed è facile comprendere come, dal punto di vista dell’armonia tonale, molti passaggi possano essere giudicati scorretti. Si aggiunga che a volte la tradizione andalusa si sovrappone alla consuetudine italiana del “suonar pieno”, che descriverò in seguito, appresa da Scarlatti durante le lezioni con Gasparini.

Un esempio, tra i tanti, dell’uso del tatracordo andaluso: nella Sonata K6 in Fa maggiore troviamo la cadenza flamenca dalla battuta 18 alla 25.

Sonata K6 (battute da 14 a 25)

Sonata K6 – Schema armonico delle battute da 18 a 25[10]

Sonata K24 (battute da 8 a 11): accordi dissonanti (battute 12-13). Possiamo notare la presenza del tetracordo andaluso nella linea del basso (Si-La-Sol♮-Fa♯ tra le battute 11 e 12)

– Procedimenti melodici e ripetizioni. È tipico della musica popolare andalusa l’utilizzo diffuso di melismi e di ripetizioni ossessive di singole note (talvolta arricchite da un’appoggiatura inferiore o superiore), di piccoli elementi musicali o di accordi. Anche la presenza di numerosi cromatismi e di intervalli espressivi contribuiscono ad aumentare l’intensità del carattere.

Lo possiamo notare nei seguenti esempi.

Sonata K263 (battute da 41 a 46): linee melismatiche

Sonata K193 (battute da 85 a 101): ripetizione di un piccolo ornamento dalla battuta 86 alla 99

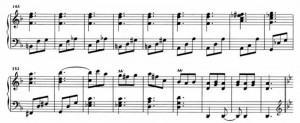

Sonata K426 (battute da 134 a 142): accordi ripetuti ossessivamente dalla battuta 138 alla 153

Sonata K426 (battute da 143 a 160): accordi ripetuti ossessivamente dalla battuta 138 alla 153

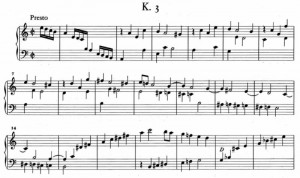

Sonata K3 (Battute da 1 a 20): cromatismo discendente dalla battuta 10 alla 15 nel pentagramma inferiore e arpeggi di settima diminuita (battute 15-16 e 19-20)

[1] Emblematiche, tra le tante, sono le vicende di Antonio Vivaldi, apprezzatissimo in vita, poi dimenticato e riscoperto solo nel Novecento, di Johann Sebastian Bach, stimato dai contemporanei, anche se giudicato un conservatore e trascurato per decenni dopo la sua scomparsa e di Georg Philipp Telemann, altro sommo musicista che iniziò a riemergere (e solo parzialmente) a partire dal secondo Novecento

[2] Quando parliamo di “dilettanti” non dobbiamo pensare all’accezione negativa che il termine ha assunto nella nostra cultura. Nel Settecento il “dilettante” era solitamente una persona di alto lignaggio e di buona formazione culturale, che faceva musica (o danza, o poesia) spesso ad un ottimo livello, per proprio diletto e non per necessità materiale. Erano “dilettanti”, probabilmente, molti dei “clienti” dei musicisti (“clienti” nel senso di coloro che si potevano permettere di pagare delle lezioni e di acquistare gli allora costosissimi spartiti). Ricordiamo che spesso i compositori facevano esplicito riferimento ai dilettanti: “Non aspettarti, o Dilettante o Professor che tu sia…” scrive Domenico Scarlatti nella prefazione agli “Essercizi”; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach dedica molte delle sue composizioni a “Kenner und Liebhaber” (competenti e dilettanti) e cita più volte i dilettanti nel suo Versuch; Johann Sebastian Bach nella prefazione alle “Inventionen und Sinfonien” si rivolge “…agli appassionati del clavicembalo…”

[3] Scarlatti fu realmente un innovatore della tecnica tastieristica. Sviluppò il discorso compositivo fino agli estremi della tastiera, diede uguale dignità alle dieci dita e sviluppò l’utilizzo di avambraccio e braccio (fino a quel momento i tastieristi sfoggiavano grande virtuosismo, ma a mano prevalentemente ferma)

[4] Nel noto dialogo, riferito da Burney, tra Scarlatti e Alexander Ludwig l’Augier, un medico austriaco, viaggiatore colto e raffinato che fu a Madrid probabilmente verso la fine del 1755 (Roberto Pagano: “Alessandro e Domenico Scarlatti. Due vite in una” – Mondadori 1985, p. 495), Domenico si dice consapevole di avere infranto quasi tutte le regole della composizione, ma, visto che le sue deroghe non offendevano l’orecchio, allora riteneva “che non ci fossero regole degne dell’attenzione di un uomo geniale, se non quella di non dispiacere l’unico senso di cui la musica è oggetto”

[5] Il titolo del contributo è: “Domenico Scarlatti: integrazione tra lo stile andaluso e lo stile italiano”

[6] Il lavoro è stato curato da Massimiliano Sala e W. Dean Sutcliffe ed è stato pubblicato da “Ut Orpheus” nel 2008

[7] La teoria medievale rovescia i sistemi: I tetracordi diventano ascendenti con la medesima successione di toni e semitoni e quindi il tetracordo “dorico” andaluso diventa il tetracordo “frigio” e viceversa

[8] Da: “Domenico Scarlatti Adventures – Essays to Commemorate the 250thAnniversary of his death” – Pag. 160

[9] Ivi, pag. 160

[10] Ivi, pag. 163

————————————————————————————

Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonatas: a multifaceted world ready to be rediscovered – 2

What happens in the musical scene during Domenico Scarlatti’s life and in the following decades after his death is a further weirdness related to the Neapolitan composer. While most of baroque composers have been forgotten due to a new musical and cultural sensitivity[1], Scarlatti has been appreciated by his contemporaries and by the main pianists over the 19th and 20th centuries.

What happens in the musical scene during Domenico Scarlatti’s life and in the following decades after his death is a further weirdness related to the Neapolitan composer. While most of baroque composers have been forgotten due to a new musical and cultural sensitivity[1], Scarlatti has been appreciated by his contemporaries and by the main pianists over the 19th and 20th centuries.

His spontaneity has been loved, opposed to Bach’s pompousness, as well as the apparent simplicity of the language, appreciated by amateurs[2] too, his taste for “cantabilità” and above all his technical-keyboard exploration that makes him a pioneer of 19th century pianism[3].

On the other hand, Scarlatti’s virtuosity and brilliance hide some features to musicians who perform Sonatas and give them an image of a bizarre and talented, but not very deep, composer.

His harmonic exploration[4] has often been “normalized” and his asymmetries have been misunderstood; his rhapsodic an improvised inspiration has often been considered messy. In an effort to classify his compositional style, some musicologists talk about Scarlatti’s Sonata like it is a proto-classical Sonata, without realizing that actually we have to look for the roots of Scarlatti’s compositions in the Italian and especially in the Neapolitan Toccata of 17th century.

We should also bear in mind that he did not write only for keyboard, indeed, but he composed operas, secular cantatas (during the years in Spain and in Portugal) and sacred music (among many, let me remind his last vocal work: the awesome Salve Regina, composed in 1756) that contains the typical originality and experimentation of Sonatas.

Let us try to explain Scarlattian weirdness looking for the two main stylistic influences within Sonatas: that which comes from the Andalusian popular tradition and that which comes from the Italian cultured tradition, considering that one of the main Scarlatti’s feature is heterogeneity. We know very few Sonatas with only one character. There are usually at least two or more issues and the deviation is often related to a few measures or to short parts of the piece; sometimes new hints are not developed but disappear as quickly as they have appeared.

SPANISH INFLUENCE

We owe Emilia Fadini the search of the Andalusian folklore elements that are in the Sonatas. Her contribute[5] inserted in “Domenico Scarlatti Adventures – Essays to Commemorate the 250th Anniversary of his death”[6] is a reference point for those who want to deepen the subject.

If we think about a Spanish influence, our thought immediately refers to that rhythm that we generally define “flamenco” and to Sonatas such as K239 in F Minor which is characterized from the beginning until the end by the typical impulse of the Spanish dance.

Sonata K239 (measures 1 to 3)

Sonata K239 (measures 11-12)

Sonata K239 (measures 15-16)

It isnotthe only rhythmic structure common to the Andalusian folk dances and to the Sonatas; Scarlatti also uses typical trends belonging to “Solea”, “Seguirya” and to “Seguidilla” that have more complex rhythmic cells that I will not treat on this occasion. But the Andalusian influence not only concerns the rhythm: above it covers the harmonic and melodic structure, the pronunciation elasticity, the formal organization, the use of repetition.

Flamenco style comes from “Cante Jondo”, developed from 15th century in the south of Spain and originated by the melting of the ancient musical Andalusian tradition, Byzantine liturgical song elements, Oriental features from the Arabic culture and suggestions brought by gypsies coming to Spain from the East. “Jondo” means “deep” and testifies of a plaintive song, that screams desperation and impotence.

Scarlatti takes from “Cante”, among other, the following elements, replicating them in a typical compositional structure belonging to the Italian tradition:

– Freedom of the introductions. Scarlatti’s Sonatas often start with an introduction disconnected from the rest of the composition: a whole phrase, a little theme, an arpeggio, a simple gesture. In the flamenco the guitar usually introduces chants and dances freely, even if the writing uses traditional time marks.

As for other features, the aim of the performer should be to put in evidence the different character of the introduction and not to integrate it with the rest of the piece, especially if it is quite different and “strange”.

The Sonata K554 (F major) starts with 2 measures and half (a succession of descending thirds) that never come back anywhere in the piece.

Sonata K554 (measures 1 to 5)

The Sonata K104 (G major) opens with two different themes (from measure 1 to 14 and from 15 to 25) and then takes a completely different direction.

Sonata K104 (measures 1 to 33)

– Scales and Andalusian cadences. Spanish claim to have maintained the theoretical principles of the Greek musical system founded on descending tetrachords (two tones and a half from the high to the low). Pure flamenco, as Spanish musicians call it, adopts as harmonic base the descending tetrachord named “Doric”, with a half tone between the third and the fourth degree[7].

The Andalusian tetrachord[8]

The common realization of the tetrachord[9]

We can see in the cadence that the succession of four chords of third and fifth could involve a series of consecutive fifthsand the use of interval of a tone and a half between the penultimate and the last triad.

Scarlatti often uses scales and Doric cadences in his Sonatas and it can be easily noticed that, if this is not contextualized or from the point of view of the tonal harmony, this method can sound weird or even incorrect.We can also add that in the Sonatas sometimes the flamenco harmony integrates with the “suonar pieno” style, that I will further explain, learned by Scarlatti in Rome by Gasparini.

One example, among many, of the use of the Spanish tetrachord: in the Sonata K6 in F major we can find the “flamenco cadenza” from measure 18 to 25.

Sonata K6 (measures 14 to 25)

Sonata K6 – Harmonic pattern of measures 18 to 25[10]

Sonata K24 (measures 8 to 11): hard chords (measures 12-13). We can see also the Andalusian tetrachord in the bass line (B-A-G♮-F♯between measures 11 and 12)

– Melodic proceedings. Some typical features of Andalusian musicarethe intensive use of melismatic features, the repetitions of a single note (sometimes accompanied by higher or lower appoggiatura) or of some small musical elements with an expressive purpose, chromaticism and expressive intervals.

We can notice them clearly in the following examples.

Sonata K263 (measures 41 to 46): melismatic phrases

Sonata K193 (measures 85 to 101): repetition of a little ornament (from measure 86 to 99)

Sonata K426 (measures 134 to 142): obsessive repetition of chords from measure 138 to 153

Sonata K426 (measures 143 to 160): obsessive repetition of chords from measure 138 to 153

Sonata K3 (measures 1 to 20): descending chromatic scale from measure 10 to 15 in the lower staff and diminished seventh arpeggios (15-16 and 19-20)

[1]Emblematic, among many others, are the stories about Antonio Vivaldi, appreciated in life, forgotten and rediscovered only in the 20th century and about Johann Sebastian Bach that was appreciated, but already considered a conservative by his contemporaries and neglected for decades after his death. Another supreme musician, George Philipp Telemann, began to re-emerge (and only partly) starting from the second half of the twentieth century

[2]When we speak about “amateurs” we must not think about the negative meaning that the term has acquired in our culture. In the 18th century the “amateur” was usually a person of high rank and good education, that practice music (or dance, or poetry) often at a great level for their own pleasure and not for material need. Among “amateurs” there were probably many musicians’ customers (“customers” in the sense of those who could afford to pay tuition and buy the then expensive sheet music). Composers often made explicit reference to the amateurs: “Don’t expect, amateur or Professor, that you’re …” writes Domenico Scarlatti in the preface to “Essercizi”; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach dedicates many of his compositions to “Kenner und Liebhaber” (competents and amateurs) and mentions several times the amateurs in his Versuch; Johann Sebastian Bach in the preface of “Inventionen und Sinfonien” turns to “…harpsichord enthusiasts…”

[3]Scarlatti was an innovator of keyboard technique. He developed the speech of composition to the farthest of the keyboard, he gave equal dignity to the ten fingers and developed the use of the forearm and arm (up to that time keyboardists showed off great virtuosity, but mostly with steady hand)

[4]In the famous dialogue, reported by Burney, between Scarlatti and Alexander Ludwig the Augier, an Austrian physician, cultured and refined traveller who was in Madrid probably towards the end of 1755, (Roberto Pagano: “Alessandro e Domenico Scarlatti. Due vite in una” – Mondadori 1985, p. 495) Domenico says to be conscious of having broken almost all rules of composition, but, given that his exceptions did not offend the ear, then he believed “that there were no rules worthy of the attention of a man of genius, than not to displease the only way by which music is the subject”

[5]The title of the contribution is: “Domenico Scarlatti: integration between Andalusian style and Italian style”

[6]The work was edited by Massimiliano Sala and W. Dean Sutcliffe and published by “Ut Orpheus” in 2008

[7]The medieval theory overturns the system: the tetrachords are processed in ascending with the same succession of tones and half-tones and then the Spanish “Doric” tetrachord becomes the “Phrygian” tetrachord and vice versa

[8]From: “Domenico Scarlatti Adventures – Essays to Commemorate the 250th Anniversary of his death” – Page 160

[9]Ivi, page 160

[10]Ivi, page 163

“Traduzione a cura della prof.ssa Fernanda Carere”