Giorgio Dellarole: musica antica per uno strumento moderno – 1 (English version of this article)

Musica antica per uno strumento moderno – 1

Con questo articolo si inaugura una nuovo spazio nel quale, con cadenza mensile, si parlerà di fisarmonica in rapporto alla musica antica.

A curarlo sarà Giorgio Dellarole, concertista e docente, che, nell’ultimo decennio, ha dedicato la maggior parte delle proprie energie allo studio e all’interpretazione del repertorio barocco, tardobarocco e classico, studiando con Emilia Fadini, Marco Farolfi e Luca Oberti e collaborando con specialisti come Michele Andalò, Fiorella Andriani, Alessandro Palmeri, Alessandro Tampieri e Saverio Villa.

Premessa

Lo studio sistematico del repertorio antico e la ricerca di una modalità interpretativa coerente e credibile, se si escludono sporadici precedenti, affondano le proprie radici nel movimento culturale avviato dalla pubblicazione del saggio di Arnold Dolmetsch “The Interpretation of the Music of the XVII and XVIII Centuries” (Londra, 1915).

Lo studio sistematico del repertorio antico e la ricerca di una modalità interpretativa coerente e credibile, se si escludono sporadici precedenti, affondano le proprie radici nel movimento culturale avviato dalla pubblicazione del saggio di Arnold Dolmetsch “The Interpretation of the Music of the XVII and XVIII Centuries” (Londra, 1915).

La parola chiave per i pionieri dell’early music è “authenticity” (fedeltà storica), un termine introdotto dallo stesso Dolmetsch che, implicitamente, bolla come “infedele” la tradizione interpretativa in voga agli inizi del XX secolo (1), ponendosi in netta contrapposizione con essa.

Basato su una ricostruzione degli strumenti antichi (in principio soprattutto il flauto dolce e la viola da gamba) il concetto di “authenticity” ispira un movimento piuttosto elitario che si afferma suscitando roventi polemiche e che non prevede l’utilizzo di strumenti non originali.

Nel corso dei decenni si moltiplicano i centri d’interesse e gli strumentisti specializzati e si accrescono le conoscenze in campo interpretativo, organologico e tecnico. L’enorme sviluppo dell’analisi musicologica, a partire dall’immediato dopoguerra, offre un ulteriore impulso alle ricerche e mette in crisi alcuni dei “dogmi” che caratterizzavano il primo movimento dell’early music, provocando la mutazione del concetto di base che diventa quello di “historically informed performance” (esecuzione storicamente informata).

Nell’ottobre del 2007, in un’intervista pubblicata dalla rivista “Sistema Musica” di Torino, Fabio Biondi, violinista e direttore d’orchestra specializzato nell’interpretazione del repertorio antico, risponde in questo modo a Diego Marangon che gli chiede di parlare del passato, del presente e del futuro della prassi originale: “Questa prassi esecutiva ha vinto una grande battaglia: creare una coscienza storica e linguistica condivisa. Ora deve vincere quella legata al feticismo dello strumento. Per il futuro vedo una grande coalizione, guidata dalla conoscenza della documentazione e dalla coscienza di chi suona: a quel punto, che Bach venga suonato con il clavicembalo o con la fisarmonica non farà alcuna differenza.”

Mi sembra evidente come Biondi, nel caso specifico, si riferisca al nostro strumento come paradosso estremo per affermare che, con la “conoscenza della documentazione” e con la consapevolezza dell’esecutore, allora addirittura con una fisarmonica si potrà suonare Bach, ma non vorrei soffermarmi su questo aspetto. Mi interessa piuttosto concentrarmi e lo farò nel prossimo articolo, sull’accento che viene posto sui termini “conoscenza” e “coscienza” nei quali risiede la chiave per una moderna e corretta interpretazione del repertorio antico (2).

Conoscenza e coscienza

A volte gli esecutori peccano di superficialità nell’esecuzione del repertorio antico.

Con tutti i limiti di una generalizzazione, mi sento di affermare come sia prassi diffusa, tra i pianisti e i fisarmonicisti, inserire nei programmi da concerto alcune composizioni barocche eseguite con lo spirito con cui si affronterebbe uno studietto sull’articolazione e con l’unico obiettivo di imitare la brillantezza del tocco cembalistico.

Le Sonate di Domenico Scarlatti sono molto amate dai tastieristi oltre ad essere emblematiche in questo senso. È vero che la leggerezza è una caratteristica del clavicembalo, ma si dimentica che esiste un’infinita varietà di articolazioni (dallo staccato al super-legato) che compongono la tavolozza a disposizione dei cembalisti. A proposito del linguaggio, inoltre, non si può negare che il virtuosismo, anche estremo, sia un elemento importante della produzione scarlattiana, ma ciò non esclude che nelle Sonate si trovino tutti i caratteri presenti nella musica operistica coeva, dai più brillanti ai più languidi e tragici. Personalmente, se dovessi citare la caratteristica principale delle Sonate di Scarlatti, non parlerei del virtuosismo, ma del grande contrasto tra i caratteri. Quasi sempre, in composizioni anche molto brevi, il compositore affianca elementi di grande contrasto ritmico, melodico e armonico. Purtroppo gli esecutori cercano abitualmente di smussarli piuttosto che di esaltarli.

Il punto è che bisogna essere consapevoli dell’opera che si affronta e per esserlo bisogna informarsi, conoscere il contesto nel quale è stata scritta e comprendere la “lingua” parlata dall’autore. Ciò è particolarmente difficile quando si ha a che fare con il repertorio barocco che non è giunto fino a noi con un percorso lineare, ma è stato prima accantonato, poi rivisitato/travisato alla luce dell’estetica romantica e solo recentemente riscoperto e approfondito con attenzione e rispetto. Le difficoltà da affrontare sono molteplici:

- Si tratta di musica molto lontana da noi, scritta per strumenti che oggi sono poco diffusi o che hanno cambiato struttura e sonorità e concepita per contesti e occasioni spesso non più riproducibili ai giorni nostri

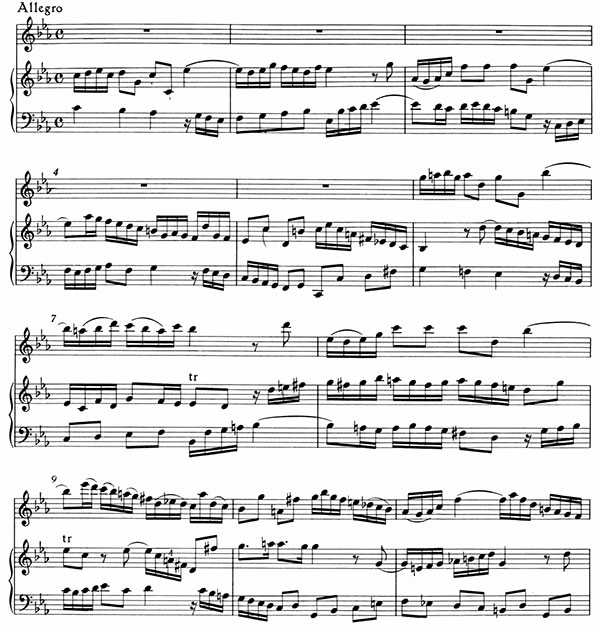

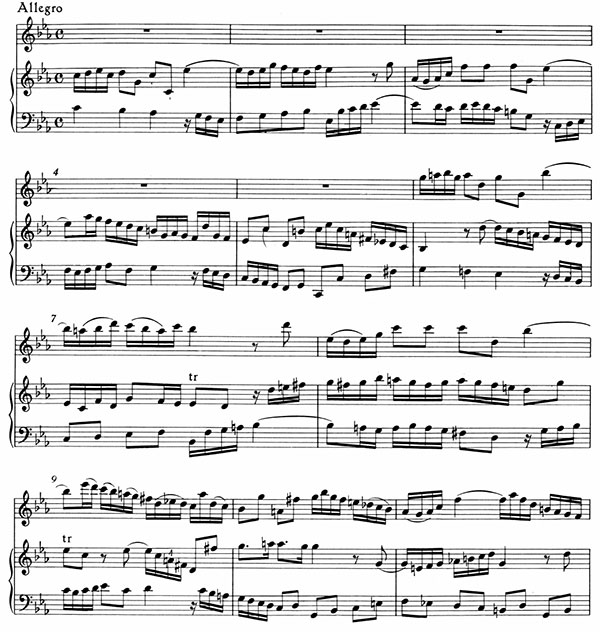

- Per diversi motivi la scrittura, in particolare quella tastieristica, è estremamente essenziale. Mancano i segni di articolazione che siamo abituati a trovare nelle partiture più recenti, spesso vengono sottintesi gli abbellimenti e la diffusione della pratica dell’improvvisazione ci impedisce di sapere precisamente cosa e come si suonasse all’epoca. Si confrontino, a tal proposito, la parte del violino e quella del cembalo obbligato nell’Allegro (2° tempo) della Sonata in Do minore BWV1017 di Johann Sebastian Bach, tratte da un’edizione fedele agli originali: a battuta 9 le semicrome del violino (nel pentagramma superiore) sono dettagliatamente raggruppate mentre lo stesso passaggio per il cembalo (batt.4) non presenta alcun segno di articolazione; similmente le semicrome del violino a battuta 7 presentano legature che non appaiono a battuta 2 nella parte del cembalo

- Non si può “mettere una sola cornice intorno ad un secolo e mezzo di musica che ha fatto della varietà e della differenza il proprio programma estetico” afferma Manfred Bukofzer nel suo “Music in the Baroque Era” (New York, 1947). Tra una Toccata di Gabrieli, una di Frescobaldi e una di Bach esistono le stesse differenze che ci sono tra una Sonata per pianoforte del primo Beethoven e una di Rachmaninoff e, per interpretare consapevolmente i diversi brani, bisogna conoscere le diverse peculiarità delle scuole, delle epoche e degli stili che caratterizzano il Barocco

- Quando si adatta un brano ad uno strumento diverso da quello per il quale è stato concepito (come fanno fisarmonicisti e pianisti quando eseguono il repertorio antico) si aprono delle opportunità, ma bisogna operare con cautela e discernimento perché si moltiplicano anche le problematiche

Per risolvere i primi tre punti penso che sia sufficiente prendere sul serio ciò che si esegue e informarsi adeguatamente. Non è una cosa da poco, considerata la vastità dell’argomento, ma si può fare. Tanto più che i documenti non sono più appannaggio di una ristretta élite, come succedeva all’epoca dei pionieri dell’early music, ma sono a disposizione di tutti. Si può risalire alle fonti, consultando trattati, lettere, prefazioni delle opere e tutto ciò che aiuti ad inquadrare il contesto storico di riferimento o affidarsi a coloro che hanno svolto un accurato lavoro di studio e ne propongono il risultato (3). L’acquisizione delle conoscenze necessarie offre, tra le altre cose, la possibilità di comprendere le fonti originali o le edizioni Urtext che le riproducono e di non essere quindi costretti ad adottare revisioni o trascrizioni che spesso non aiutano a cogliere il significato dell’opera.

A proposito del quarto punto riporto le parole che Marco Farolfi (4), cembalista, pianista e didatta, nonché specialista del repertorio antico, ha utilizzato per descrivere il lavoro che abbiamo svolto insieme negli anni passati. Con questo pensiero, che condivido pienamente, chiudo il mio primo intervento su “strumentiemusica.com”, ringraziando Gianluca Bibiani per lo spazio che mi offre e per la stima, ricambiata, che mi ha manifestato.

“La pratica dell’esecuzione del repertorio antico sugli strumenti moderni è piuttosto diffusa e controversa. Da un certo punto di vista possiamo attribuire allo strumento un ruolo di “mediatore” che veicola il messaggio musicale e possiamo quindi considerarlo un intermediario sul quale prendono forma le idee musicali dell’interprete che se ne avvale. Se da soggetto lo strumento diventa oggetto osserveremo che la musica si identifica come vero soggetto conduttore. Di conseguenza la scelta di un “mediatore strumentale” attuale non impedirà (osservando da questa prospettiva) di esprimere comunque l’opera d’arte musicale nella maniera più rispettosa possibile dei suoi caratteri stilistici peculiari. Lo studio della prassi esecutiva, delle maniere proprie e del linguaggio con cui riproporre al meglio la composizione ci darà comunque la possibilità di esprimere attraverso qualsiasi strumento, originale o moderno, l’essenza stessa e i migliori contenuti artistici di un’opera musicale del passato. L’idea interpretativa che ho ricercato durante il lavoro con Giorgio si riassume perciò nella definizione di una proposta musicale che ponga l’opera in primo piano rispettandone la natura musicale e che veda lo strumento – “mediatore moderno” – unicamente come oggetto della sua realizzazione. Lo strumento storico può forse aiutare a ricostruire l’ambientazione sonora verosimilmente più simile a quella immaginata dal compositore, ma oggi, trascorsi centinaia di anni, molti strumenti nuovi arricchiscono la nostra vita musicale e in quest’ottica nessuno strumento può dirsi veramente più giusto o meno appropriato se non prevarica sulla natura e sui contenuti della musica a cui dà vita.”1) All’epoca e ancora oggi, parzialmente, l’estetica tardo-romantica dominava l’ambiente musicale ed era talmente forte e radicata da condizionare pesantemente la lettura delle composizioni barocche 2) Con “repertorio antico”, in un’accezione del tutto personale, faccio riferimento alla musica scritta dagli albori degli strumenti a tastiera fino a Mozart e Haydn 3) Nel prossimo articolo parlerò dei trattati e dei testi più importanti in maniera diffusa; per il momento mi limito a suggerire la lettura de “Il clavicembalo”, Bellasich, Fadini, Granziera, Leschiutta – EDT (2005) che, nelle sue quattro parti, presenta gli strumenti a tastiera a corde pizzicate e percosse, fa una panoramica sull’accordatura e sui temperamenti storici, tratta di notazione e mensuralità dal Trecento al Settecento e descrive le diteggiature utilizzate dalle diverse scuole nel corso delle epoche 4) Per conoscere Marco Farolfi suggerisco di ascoltare il Volume 6 della raccolta “Domenico Scarlatti – Complete Sonatas”, in corso di pubblicazione da parte dell’etichetta “Stradivarius”. Su “You Tube” si trovano altre registrazioni tra le quali, per restare su Scarlatti, segnalo quelle della Sonata in Fa minore K462 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkSj4802TyQ) e della Sonata in Fa minore K463 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CECXEOWU6l8)

Early music for a modern instrument -1

With this article we inaugurate a new space in which, on a monthly basis, we will deal with accordion in relation to early music.

Giorgio Dellarole, concert performer and teacher, will edit this work. Mr. Dellarole, over the past decade, has devoted most of his energies to the study and interpretation of the Baroque, late Baroque and Classical repertoire, studying with Emilia Fadini, Marco Farolfi, Luca Oberti and collaborating with some specialists such as Alessandro Tampieri, Alessandro Palmeri, Michele Andalò, Fiorella Andriani and Saverio Villa.

Preamble

If we exclude sporadic backgrounds, we can consider that the systematic study of the ancient repertoire and the research of a coherent and credible interpretative mode sink their roots in a cultural movement initiated by the publication of the essay written by Arnold Dolmetsch “The Interpretation of the Music of the XVII and XVIII Centuries” (London, 1915).

If we exclude sporadic backgrounds, we can consider that the systematic study of the ancient repertoire and the research of a coherent and credible interpretative mode sink their roots in a cultural movement initiated by the publication of the essay written by Arnold Dolmetsch “The Interpretation of the Music of the XVII and XVIII Centuries” (London, 1915).

The keyword for the pioneers of early music is “authenticity”, a term introduced by Dolmetsch that, implicitly, labels as “infidel” the interpretative tradition in vogue in the early XX century[1]and that therefore is in clear contrast with it.

Based on a reconstruction of ancient instruments (at the beginning especially the recorder and the viola da gamba) the concept of “authenticity” inspires a rather elitist movement, which arouses controversies and excludes the use of non-original instruments.

Over the decades, interest on this matter increases and knowledge in interpretative, organologic and technical field are enhanced. The development of musicology, starting from the immediate post-war period, provides a further impetus to researches and puts in crisis some of the “dogmas” that characterised the first movement of early music, causing in this way the mutation of the basic concept, which turns into “historically informed performance”.

In October 2007, in an interview published by the magazine “Sistema Musica” of Turin, Fabio Biondi, violinist and conductor specialized in the interpretation of early music, says to Diego Marangon: “The study of how the early music repertoire was played has achieved a great victory, by sharing its history and language. Now, it has to win over the preconception of the instrument. I can envisage a great coalition coming about in the future, guided both by a knowledge of the score and the musician’s awareness, where Bach can be played equally well on the harpsichord or the accordion”.

Biondi in his speech affirms that with “knowledge of the score” and with the awareness of the performer even with accordion it is possible to play Bach; anyway, I would not dwell on this aspect.

I would rather prefer to concentrate my attention, and I will do it in my next article, on the emphasis that is placed on the words “knowledge” and “awareness”, in which, in my opinion, it resides the key for a modern and correct interpretation of the ancient repertoire.[2]

Knowledge and awareness

In my opinion, it happens sometimes that performers are superficial when they play the ancient repertoire.

I would say that it is common practice, not only among accordion players, to include in a concert program some Baroque compositions which are performed with the spirit generally adopted to deal with a study on articulation, looking to imitate the brilliance of the harpsichord touch.

Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonatas are very popular among keyboard players as well as being emblematic in this sense. It is true that the lightness is a feature of the harpsichord, but it is forgotten that there is an infinite variety of articulations (starting from the “staccato” to the “super-legato”) at harpsichordists disposal. Speaking of language, there is no denying that the virtuosity, even extreme, is an element widely used by Scarlatti, but this fact does not exclude that in his Sonatas there are all the characters that feature in the contemporary Opera, from the brightest to the most pathetic and tragic. If I had to mention the main feature of Scarlatti’s Sonatas, I would not speak about virtuosity, but rather about the presence of two or more characters that often are in rhythmic, melodic or harmonic conflict. Unfortunately, many performers try to level out differences rather then emphasize them.

It is really important to be aware of the work that you are dealing with and you have to be informed, to know the context in which it was written and understand the “language” spoken by the author. This is especially difficult when you deal with the Baroque repertoire because it has not come down to us with a linear path, but it has been shelved before, and then revisited/misrepresented in the light of romantic aesthetics and only recently rediscovered and more carefully and respectfully examined. There are several problems to face:

- It is very old music, written for old instruments that nowadays, probably, have been modified in their structure and because of this, they sound differently in relation to the past

- For several reasons, the writing, in particular the one concerning keyboard instruments, is extremely essential[3]. Infact it lacks of “legature” that we are used to find in the most recent scores. Moreover, often ornaments are implied and the diffusion of the practice of improvisation prevents us from knowing exactly what and how music sounded at that time

![]() Manfred Bukofzer in his “Music in the Baroque Era” (New York, 1947) states that it is not possible to simplify a century and a half of music that has been characterized by an extreme variety. Among a Toccata of Gabrieli, one of Frescobaldi or Bach, there are the same differences that exist between a Sonata for piano of Beethoven and one of Rachmaninoff. In order to consciously play the different scores, you have to know the different characteristics of schools, eras and styles that characterize the Baroque period

Manfred Bukofzer in his “Music in the Baroque Era” (New York, 1947) states that it is not possible to simplify a century and a half of music that has been characterized by an extreme variety. Among a Toccata of Gabrieli, one of Frescobaldi or Bach, there are the same differences that exist between a Sonata for piano of Beethoven and one of Rachmaninoff. In order to consciously play the different scores, you have to know the different characteristics of schools, eras and styles that characterize the Baroque period- Whenever you make a transcription from harpsichord to the piano or to the accordion, many opportunities show up, but you have to act with caution and discernment because in this case problems multiply

In order to solve the first three points, I think it is enough to take seriously what you do and to get appropriate information. Given the vastness of the subject it is not an easy thing, but it can be done. The documents are no longer the preserve of a small elite as it was the case at the time of the pioneers of early music, but they are at everyone disposal. Sources can be traced by consulting treaties, letters, prefaces of scores and everything that helps to frame the historical context or by relying on those who have done an accurate study and have proposed their results[4]

The acquisition of the necessary knowledge provides, among other things, the ability to understand the original sources or Urtext editions that reproduce them and the fact not to be forced to adopt revisions or transcriptions that often do not help to understand the meaning of the scores.

Concerning the fourth point, I quote the words that Marco Farolfi[5], harpsichordist, pianist and teacher, as well as specialist of the early repertoire, used to describe the work that, over the years, we have done together. With this thought, which I fully support, I close my first speech on “strumentiemusica.com”. I am grateful to Gianluca Bibiani for the space he offered me and for the esteem that he has expressed, which of course I reciprocate.

“Playing early music repertoires on modern instruments is both quite popular and controversial.

From one point of view we can say that the instrument has the role of a “mediator” which conveys the musical message and we can therefore consider it as an intermediary between the formation of musical ideas and interpretation of the musician. If the instrument become a “medium”, the music gets the “matter”.

But this does not mean that the modern “instrumental mediator” will not take the greatest possible care to respect the style and character of the musical pieces.

The study of musical language and methodology means that it is possible to express the feelings of early music using either original or modern instruments.

During my work with Giorgio I discovered that the musical composition was always in the foreground and the “modern mediator” may be the perfect way to perform these compositions.

The use of historical instruments to play early music can help to recreate the atmosphere which the composer would have wanted. But today after the passage of hundreds of years and the use of modern instruments we can say that any instrument can be adapted to any musical style and no one can say which instrument is more appropriate if it doesn’t prevail on the nature and on the contents of the music that it creates”.

I am grateful to Marta Cogotti for her translation

1) At that time and even today the late-Romantic esthetic dominated the music scene and influenced the performance of Baroque pieces 2) With “ancient repertoire, in a very personal sense, I refer to the music written since the birth of keyboard instruments until Mozart and Haydn 3) In the next article I will talk about the treaties and of the most important texts; for the moment I simply suggest to read “Il clavicembalo”, Bellasich, Fadini, Granziera, Leschiutta – EDT (2005) that, in its four parts, presents the ancient keyboard instruments, the temperaments, the mensural notation and the different historical fingerings 4) About Marco Farolfi: “Domenico Scarlatti – Complete Sonatas” – Stradivarius – Vol. 6Domenico Scarlatti - Sonata in F minor K462 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkSj4802TyQ) and Sonata in F minor K463 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CECXEOWU6l8)