Giorgio Dellarole: musica antica per uno strumento moderno – 6 (English version of this article)

L’INTERPRETAZIONE

Proseguiamo il discorso iniziato nel quinto articolo e analizziamo qualche altra Invenzione a due voci di J.S. Bach.

L’Invenzione n.4 in Re minore BWV 775 è probabilmente un brano piuttosto scorrevole. Lo deduciamo dall’indicazione 3/8 che spesso è associata ad andamenti brillanti, da una scrittura sostanzialmente uniforme nella quale prevalgono i gradi congiunti e dall’assenza di intervalli particolarmente espressivi che potrebbero indicare momenti di maggiore cantabilità. Si notano similitudini con il Passepied (ad esempio quello della Suite inglese N.5 in Mi minore) e si deduce un andamento alla battuta.

Come consigliato nel quarto articolo, possiamo iniziare l’analisi individuando i momenti di Tesi e i momenti di Arsi nelle prime battute e applicando poi le nostre deduzioni all’intera composizione.

La consuetudine potrebbe condurci a battezzare la prima battuta come portatrice dell’accento tonico e la seconda come “levare”, ma un’analisi più attenta della scrittura ci fa pensare che il brano inizi in “levare” e abbia il suo appoggio forte sulle battute “pari”. Notiamo infatti che il flusso delle semicrome che si muovono per grado congiunto è interrotto solamente dai due intervalli di settima diminuita che precedono e seguono il Do# della seconda battuta, evidenziandolo chiaramente e suggerendoci un appoggio proprio in quel punto.

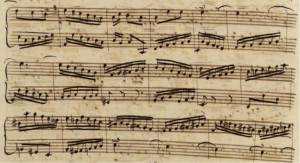

Invenzione n. 4 – Battute 1-2

È evidente il cambiamento di accentuazione con l’Emiolia[1] nella cadenza delle misure 16 e 17.

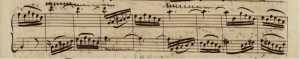

Invenzione n.4 – Battute 16-17 – Emiolia

A livello pratico possiamo condurre le semicrome della prima battuta con un tocco quasi legato o leggermente sciolto (se “pronunciassimo” troppo le singole semicrome rischieremmo di moltiplicare gli impulsi e di appesantire l’andamento), separare chiaramente il Sib dal Do#, appoggiare il Do# restando sul tasto un po’ più a lungo dello stretto valore di sedicesimo e quindi, dopo aver separato il Do# dal successivo Sib, riprendere il leggero legato “scivolando” verso la terza battuta e recuperando, con un piccolo incremento di velocità, il tempo “perso” nelle due articolazioni e nella breve sosta sul Do#.

Invenzione n.4 – Battute 1-2-3-4

Vale la pena di soffermarsi, prima di passare ad un’altra Invenzione, sui due lunghi abbellimenti alle battute 19-20-21 (a destra) e 29-30-31-32-33 (a sinistra).

Le fonti, nella situazione specifica e in situazioni simili, riportano indicazioni diverse[2].

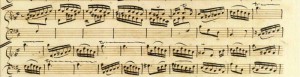

Invenzione n.4 da batt. 15 a batt. 32 – Manoscritto appartenuto a W.F. Bach con annotazioni dello stesso Johann Sebastian Bach (il pentagramma superiore è in chiave di violino francese, appoggiata sul primo rigo e non sul secondo, oggi caduta in disuso)

Invenzione n.4 da batt. 11 a batt. 32 – Altro manoscritto citato come autografo di J.S. Bach

Invenzione n.3 da batt. 25 a batt. 33 – Manoscritto appartenuto a W.F. Bach con annotazioni dello stesso Johann Sebastian Bach (il pentagramma superiore è in chiave di violino francese, appoggiata sul primo rigo e non sul secondo, oggi caduta in disuso)

Invenzione n.3 da batt. 18 a batt. 36 – Altro manoscritto citato come autografo di J.S. Bach

Non dobbiamo dimenticare che la durata e il carattere degli ornamenti sono condizionati dalla durata della nota reale e dal carattere del brano e non solo dal segno che viene utilizzato.

Il carattere grafico che noi associamo al mordente[3] (che ritroviamo nelle battute 19, nel pentagramma superiore e 29, nel pentagramma inferiore, del primo manoscritto citato relativo all’Invenzione n.4) non deve suggerire un’esecuzione rapida e brillante dell’ornamento. Il contesto e l’analisi degli altri frammenti, che riportano lunghi tratti oscillatori, ci fanno capire che probabilmente è necessario eseguire un lungo trillo o qualcosa di simile, che permette al clavicembalo (e al pianoforte moderno) di sostenere il suono, diventando elemento strutturale nell’esecuzione fedele del portato compositivo.

Partendo da questo assunto io eseguirei un trillo prolungato anche con uno strumento come la fisarmonica che non ha l’esigenza pratica di sostenere un suono che altrimenti si estinguerebbe. Personalmente preferisco iniziare più lentamente l’oscillazione e incrementare la velocità del trillo, mantenendo le due mani indipendenti e chiudendo il trillo stesso prima della conclusione della battuta. Da misura 29, visto che il trillo si trova a sinistra ed è più lungo, non escluderei di sostenerlo per un paio di battute, di fermarsi sul Mi e di riprenderlo per poi chiuderlo con le stesse modalità del precedente.

L’Invenzione n.6 in Mi maggiore BWV 777 presenta delle caratteristiche differenti da quella appena analizzata pur essendo, come la precedente, in 3/8. I valori molto brevi e la sincopazione (che dà vita ad una sorta di “rubato”) impongono un andamento non rapidissimo che permetta di godere delle piccole dissonanze che nascono e che si sciolgono, ma non bisogna farsi trarre in inganno dal cromatismo discendente, che potrebbe far pensare ad un carattere drammatico. Se non ci fermiamo alle prime battute, ma analizziamo l’intera composizione, vediamo che, specialmente nella seconda parte dell’Invenzione, i piccoli mordenti in levare scritti in note reali vivacizzano molto l’andamento. C’è un contrasto di “affetti” tra la brillantezza degli ornamenti e il cromatismo apparentemente doloroso, ma il carattere dominante è sicuramente il primo. Se analizziamo la consuetudine bachiana (a partire dal Clavicembalo ben temperato, soprattutto per quanto riguarda il Preludio e fuga n.9 in Mi maggiore dal Primo Libro) e dei suoi contemporanei, verifichiamo che la tonalità di Mi maggiore è spesso il luogo della serenità, della tenerezza e della cantabilità. Questo brano non fa eccezione e sembra quasi una “galanteria” per flauto di Quantz o di Graun.

I trentaduesimi non indicano virtuosismo; si tratta semplicemente di piccoli mordenti scritti in note reali da eseguire in maniera morbida, calandoli nel contesto della composizione.

Io inizierei legando leggermente la parte destra e separando gli ottavi della sinistra. Teniamo presente che una delle maniere più semplici per accentare (nel senso di “evidenziare”) una nota è di separarla dalla precedente; più sarà ampia la separazione, più evidente sarà l’accento. I fisarmonicisti possiedono uno strumento che, con il mantice, può proporre una grande varietà di inflessioni. Purtroppo, con questa modalità, l’accento viene attribuito alla parte destra come alla sinistra e può capitare, a maggior ragione nelle composizioni polifoniche, che le diverse linee richiedano un’articolazione differenziata. Naturalmente non sto sostenendo che non si debbano usare le possibilità dinamiche e accentuative del mantice, ma ritengo importante ricordare che ci sono modi diversi per dare evidenza alle note.

Apro una piccola parentesi a proposito degli “accenti” conseguenti alle articolazioni per ricordare che Couperin prima e Rameau successivamente, probabilmente codificando una tradizione seicentesca francese, inserirono la separazione tra i suoni addirittura tra gli ornamenti, definendola “Suspension” e indicandola come segue.

F. Couperin – Primo libro dei “Pieces de Clavecin” – 1714

J.Ph. Rameau – “Pieces de Clavessin avec une methode pour la mechanique des doigts” – 1724

Se noi separiamo gli ottavi della sinistra, creiamo dei piccoli “accenti” nei momenti di scontro tra i due manuali. Questi urti vengono risolti dalla parte destra che, legando, scende dolcemente sulla consonanza. Come codificato, tra gli altri, da C.Ph.E. Bach e da Quantz[4], la dissonanza viene così evidenziata rispetto alla consonanza. Quando le crome sincopate non si muovono con cromatismi (ad esempio nel pentagramma superiore a battuta 9 e a battuta 11) possiamo articolarle un poco, ma sempre meno delle crome che “rompono” le sincopi stesse creando gli “scontri”. È il “disegno” della linea melodica che ci suggerisce la dimensione di ciascuna separazione: sarà minore tra i movimenti per terze nel pentagramma superiore alla battuta 9 e più ampia nel salto di ottava tra i Fa# all’inizio della battuta 11 (sempre nel pentagramma superiore). In questo modo si viene a creare naturalmente quell’ondulazione, della quale abbiamo ampiamente trattato[5], che dà vita e direzione all’esecuzione.

L’Invenzione n.14 in Sib maggiore BWV 785 ci offre l’occasione per proseguire il discorso sugli abbellimenti, che approfondirò nel prossimo articolo.

I gruppi di biscrome non sono altro che “mezzi circoli”, dei gruppetti di origine vocale con uno sviluppo che copre una terza; non si tratta di momenti di virtuosismo, ma, di ornamenti scritti per esteso[6]. Da una parte, quindi, è necessario prendersi il tempo necessario a pronunciare correttamente i mezzi circoli, dall’altra bisogna comunque mantenere un andamento scorrevole in virtù della pulsazione binaria della misura. La tonalità di Sib maggiore è solitamente utilizzata per esprimere un carattere gioioso, ma è spesso associata anche ad un certo impeto e la composizione è sicuramente vivace e ricca di echi e di arpeggi.

Le semicrome possono essere eseguite sciolte e leggere oppure articolate a due, ma la cosa importante è non appesantire troppo il discorso musicale.

Ancora un piccolo suggerimento sull’esecuzione dei “mezzi circoli” prima di chiudere l’articolo: dovendo, come ho scritto, ricercare un andamento legato e leggermente irregolare nella pronuncia dell’abbellimento io curerei la diteggiatura e il gesto. In particolare utilizzerei per tutti i “gruppetti” le tre dita centrali (2-3-4-3-2 o 4-3-2-3-4)[7] e, riducendola al minimo, accompagnerei l’articolazione con una piccola rotazione del polso che può contribuire a caratterizzare in maniera efficace l’ornamento.

Concludo segnalando ai lettori un’interessante masterclass sul Clavicembalo ben temperato di J.S. Bach che il pianista Gianluca Luisi terrà nei giorni 19 e 20 maggio presso il Conservatorio di Parma. Si tratterà della seconda occasione, in pochi mesi, di approfondire lo studio dei due libri che compongono l’importante opera bachiana e seguirà la masterclass curata dal clavicembalista Enrico Baiano. I due appuntamenti fanno parte del “Laboratorio Tastiere e Prassi Storiche” che vede coinvolti il Dipartimento Tastiere e il Dipartimento di Musica Antica del “Boito” e, in particolare, i docenti di clavicembalo, pianoforte e fisarmonica.

L’obiettivo è di andare alle radici del linguaggio bachiano individuando i caratteri fondamentali delle opere trattate e, nel contempo, di comprendere come ciascuno degli strumenti coinvolti possa esprimere gli “affetti” caratteristici dei brani rispettando le proprie peculiarità meccaniche ed espressive.

Ringrazio Emilia Fadini e Marco Farolfi per i preziosi suggerimenti e per i riferimenti alle fonti.

[1] L’Emiolia (termine di origine greca che indica il rapporto 3/2) è una formula ritmica utilizzata in cadenza che prevede un mutamento da una suddivisione binaria ad una ternaria. Nel nostro caso, considerando il nucleo di due battute da 3/8, passiamo dai due accenti (uno su ogni misura) che caratterizzano il brano, ai tre accenti (uno ogni due ottavi) della cadenza delle battute 16-17 [2] Ricordiamo che gli aspiranti che venivano accettati come allievi da J.S. Bach dovevano, come prima cosa, copiare tutto il materiale (Invenzioni, Suites, Clavicembalo ben temperato…) che avrebbero poi utilizzato nel corso degli studi. Quindi abbiamo molte versioni, tutte attendibili, degli stessi brani [3][4] Vedere terzo articolo per i riferimenti sui trattati citati [5] Vedere il quarto articolo per il discorso su Tesi e Arsi [6] Per gli ornamenti i riferimenti da tenere presenti sono il canto e l’improvvisazione. Nel limite del possibile, bisognerebbe cercare di eseguirli sempre legati (all’interno del proprio sviluppo) e in maniera non eccessivamente meccanica [7] Questa diteggiatura può essere adottata sulle fisarmoniche a tastiera e su quelle a bottoni e si può utilizzare anche sul manuale sinistro per terze minori

Giorgio Dellarole: early music for a modern instrument – 6

THE INTERPRETATION

Let’ s continue the work begun in the fifth article and let’s analyse some other Two-Part Invention by J.S. Bach.

The Invention No.4 in D minor BWV 775 is probably a fluid musical piece. We deduce it from the indication 3/8 which is often associated with brilliant performances, from a substantially uniform writing in which prevail conjunct motions and from the absence of particularly expressive intervals that could indicate moments of lyricism. There are some similarities with the Passepied (for example the one of the English Suite No. 5 in E minor) and we can deduce a pulsation for every bar.

As recommended in the fourth article, we can begin our analysis by identifying the moments of Thesis and the moments of Arsi in the first measures; then we’ll follow the same rules for the whole piece.

The practice could lead us to identify the first beat as the bearer of the tonic accent, but a closer analysis of the writing makes us think that the piece begins on hand up and has his strong beat on the “even” measures. We note in fact that the flow of sixteenth notes which move in conjunct motion is interrupted only by two intervals of diminished seventh that precede and follow the C-sharp of the second measure, clearly highlighting it and suggesting a proper emphasis at that point.

nvention No. 4 – Measures 1-2

It is evident the change of accentuation with the “Emiolia”[1] in the cadence of the measures 16 and 17.

Invention No. 4 – Measures 16-17 – Emiolia

On a practical level, we can conduct the sixteenth notes of the first measure with an almost tied or slightly articulated touch (if we pronounce too much the individual sixteenths we risk to multiply the impulses and to weigh the trend). Then we can clearly separate the B-flat from the C-sharp, stay on the C-sharp a little longer than the narrow value of the sixteenth and then, after having separated the C-sharp from the next B-flat, resume the light “legato” by “slipping” towards the third bar and by recovering, with a small increase of speed, the “lost” time in the two articulations and in the brief stop on the C-sharp.

Invention No.4 – Measures 1-2-3-4

It is worth dwelling, before moving on to another Invention, on the two long ornaments of the measures 19-20-21 (on the right) and 29-30-31-32-33 (on the left). The sources, in the specific case and in similar situations, contain different information[2].

Invention No. 4 from measure 15 to measure 32 – Manuscript belonged to W.F. Bach with notes by J.S. Bach (the upper stave has a French G-clef, placed on the first line and not on the second, that is no longer in use)

Invention No. 4 from measure 11 to measure 32 – Manuscript quoted as an autograph of J.S. Bach

Invention No. 3 from measure 25 to measure 33 – Manuscript belonged to W.F. Bach with notes by J.S. Bach (the upper stave has a French G-clef, placed on the first line and not on the second, that is no longer in use)

Invention No. 3 from measure 18 to measure 36 – Manuscript quoted as an autograph of J.S. Bach

We must not forget that the length and character of the ornaments are influenced by the duration of the central note and by the character of the piece and not just by the sign that is used.

The graphic character that we associate with the mordent[3] (measure No. 19 on the upper stave and measure No. 29 on the lower stave from the first quoted manuscript) must not suggest us a rapid and brilliant performance of the ornament.

The context and the analysis of the other fragments, which contain long trills, make us understand that we need to play a trill or something similar, which becomes a structural part of this composition and allows to the harpsichord (and to the modern piano) to sustain the sound.

Starting from this assumption I would perform a prolonged trill even with an instrument like the accordion that has no practical need to support a sound that otherwise would disappear.

Personally, I prefer to start the oscillation slowly and to increase the speed of the trill, keeping the hands independent and closing the trill before the conclusion of the measure.

From the measure 29 as the trill is on the left and is longer, I would not rule out to support it for a couple of bars, to stop on the E and to take it back and then close it with the same previous modes.

The Invention No.6 in E major BWV 777 presents different characteristics compared to the one just analysed, even if they are both in 3/8. The very brief values and syncopation (that gives life to some kind of “rubato”) impose a not very fast performance which allows to enjoy the small dissonances that arise and that after will melt, but we mustn’t be misled by the descending chromaticism that could suggest a dramatic character.

If we don’t stop to the first measures and we take into consideration the whole score, we see that, especially in the second part, the little upbeat mordents live up this piece.

There is a contrast of “affetti” between the brilliant ornaments and the painful chromaticism, but the principal character is the first.

If we analyse the practice of Bach (from the Well Tempered Clavier, especially with regard to the Prelude and Fugue No.9 in E major from the First Book) and of his contemporaries, we verify that the tonality of E major is often a place of serenity, tenderness and lyricism. This piece is no exception and it looks like a “galanteria” for flute from Quantz or Graun.

The thirty-second notes do not indicate virtuosity; they are simply small mordents written in real notes to perform in a soft way, setting them in the context of the composition.

I’d begin with a slightly tie on the right side and separating the octaves of the left. Keep in mind that one of the simplest ways to accent (in the meaning of “highlighting”) a note is to separate it from the previous one; more the separation is wider, the more obvious will be the accent. The accordionists have an instrument that, with the bellows, may propose a big variety of inflections. Unfortunately, with this mode, the emphasis is attributed to both the hands and it may happen, a fortiori in polyphonic compositions, that the different lines require a differentiated articulation.

Of course I am not advocating that we should not use the dynamic possibilities of our bellows, but I consider it important to remember that there are different paths to highlight the notes.

I open a small parenthesis about the “accents” resulting from the articulations to remember that first Couperin and then Rameau, probably by encoding a French seventeenth-century tradition, inserted the separation between the sounds even among ornaments, calling it “Suspension” and indicating it as follows.

F. Couperin – First book of “Pieces de Clavecin” – 1714

J.Ph. Rameau – “Pieces de Clavessin avec une methode pour la mechanique des doigts” – 1724

If we separate the eight notes of the left, we create some small “accents” in moments of clash between the two parts. These dissonances are resolved on the right line that, tying, descends gently on the consonance. As coded, among others, by C.Ph.E. Bach and by Quantz[4], the dissonance is then highlighted more than the consonance. When the syncopated eight notes do not move with chromaticisms (for example in the upper stave at the measures 9 and 11) we can articulate them a little, but always less than the eighth notes that “break” the syncopations by creating “collisions.” It is the “drawing” of the melodic line that suggests the size of each separation: it will be less between the thirds in the upper stave at measure 9 and wider between the two F-sharp at the beginning of measure 11 (always in the upper stave). In this way we are able to create that waviness, which we have spoken about[5], that gives life and direction to the performance.

The Invention No.14 in B-flat major BWV 785 gives us the opportunity to continue the discussion on ornamentation that I will deal with in the next article.

The sixteenths notes groups are nothing more than “mezzi circoli”, some ornaments of vocal origin with a development that covers a third; it is not about moments of virtuosity, but of ornaments written in full[6]. On one hand, therefore, it is necessary to take the time to properly pronounce the “mezzi circoli”, on the other you must still maintain a fluid performance for the binary pulsation of the measure.

The tonality of B-flat major is usually used to express a joyful character, but it is often associated with a certain momentum and this piece is definitely full of echoes, arpeggios and liveliness.

The sixteenths notes can be played untied and lightly or with a tie between every two notes, but it is important that the musical discourse never stops flowing.

Just a little tip on the performance of “mezzi circoli” before closing the article: if we have to search for a bound and slightly irregular trend in the pronunciation of the ornaments I would focus on the fingering and on the gesture.

In particular I would use for all “groups” the three middle fingers (2-3-4-3-2 or 4-3-2-3-4)[7] and, by reducing it to the minimum, I would accompany the articulation with a small rotation of the wrist that can help to effectively characterize the ornament.

I conclude giving to my readers a news about an interesting masterclass on the Well Tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach. The pianist Gianluca Luisi will hold on May 19th and 20th a masterclass at the Conservatory of Parma. It will be the second occasion, in a few months, to deepen the study of this important work by Bach and it will follow the masterclass held by the harpsichordist Enrico Baiano.

These two dates are an integral part of the “Laboratorio Tastiere e Prassi Storiche”, a project that involves the “Keyboards Department” and the “Early Music Department” of the “A. Boito” Conservatory of Parma and the Harpsichord, Piano and Accordion teachers. The objective is to go to the roots of Bach language, identifying the character of his compositions and understanding how each of the involved instruments can perform the peculiar “affetti” of this repertory, complying with its own technical and expressive skills.

I thank Emilia Fadini and Marco Farolfi for valuable suggestions and references to sources.

(Translated by Marta Cogotti)

[1]The Emiolia (Greek term that indicates the 3/2 ratio) is a rhythmic formula used in cadence which involves a change from a binary subdivision to a ternary. In our case, considering the nucleus of two measures, we pass from the two accents (one on each measure) that characterize the piece, to the three accents (one on every two octaves) of the cadence of the measures 16-17 [2] Recall that the aspirants who were accepted as students by J.S. Bach had, at first, to copy all the material (Inventions, Suites, Well-Tempered Clavier ...) before using it for their studies. So we have many versions, all reliable, of the same pieces [3][4] See the third article for the references on the quoted treatises [5] See the fourth article about Thesis and Arsi [6] For the ornaments the references to keep in mind are the singing and improvisation. If possible, you should always try to tie them (within their development) and in a manner not too mechanical [7] This fingering can be adopted on the piano accordion and on the (wrongly called) chromatic accordion and can also be used on the left hand with minor thirds